‘보그’가 탄생하기 이전의 시대

암스테르담 레이크스 미술관에서 옛 패션과 의상 그림, 그리고 패션 매거진의 발전을 조우하다.

5명의 여성들. 1명은 웨딩드레스를 입고 있다. 그 뒤쪽에서는 두 남성이 대화를 나누고 있다. 1858년 10월호, 손으로 채색한 판화, J 보나르, 쥴스 데이비드(1808-1892), 라무뢰

그는 깃털모자에 한껏 부풀린 소매를 한 코트, 프릴 달린 바지와 화려한 부츠를 입고 있었다. 그녀는 관능적인 나비리본 보디체와 함께 소파 전체를 뒤덮을 크기의 풀스커트와 시폰 헤드피스를 매치했다.

그래, 화려한 80년대였다. 바로 1680년대 말이다. 모든 프릴과 고상한 척이 사라지기 직전, 루이 14세의 방탕한 주지육림이 함께 하던 그 시기 말이다.

나는 암스테르담의 레이크스 미술관에서 아마도 지나간 패션 트렌드보다 훨씬 여러 번 상영되었을 프랑스혁명사에 관한 속보를 마주쳤다. 레이크스 미술관에서는 9월 27일까지 <뉴 포 나우(New for Now)>가 열린다. 이 전시회는 연필과 붓으로 설명하는 역사에 대해 눈과 귀를 트여줄 것이다.

<보그>가 있기 전에 유행하던 의상 드로잉은 전시회를 멋지고 유익하게 만들어줬고 패션을 삶의 세계로 이끌기 위해 과감한 쇼맨십이나 드라마틱한 세팅은 필요치 않다는 걸 증명했다.

즐겁고 섹슈얼한 숨바꼭질 놀이를 암시하는 푸르게 우거진 포도카르푸스 나무가 전시공간 한가운데에 줄 맞춰 심어져 있었다. 전시디자이너이자 공동 큐레이터인 크리스찬 보르스틀랩(Christian Borstlap)은 이 전시공간을 통해 변화하는 패션과 라이프스타일에 관한 이야기를 잡지시대 이전에 존재했던 세밀한 드로잉 안에 담아냈다.

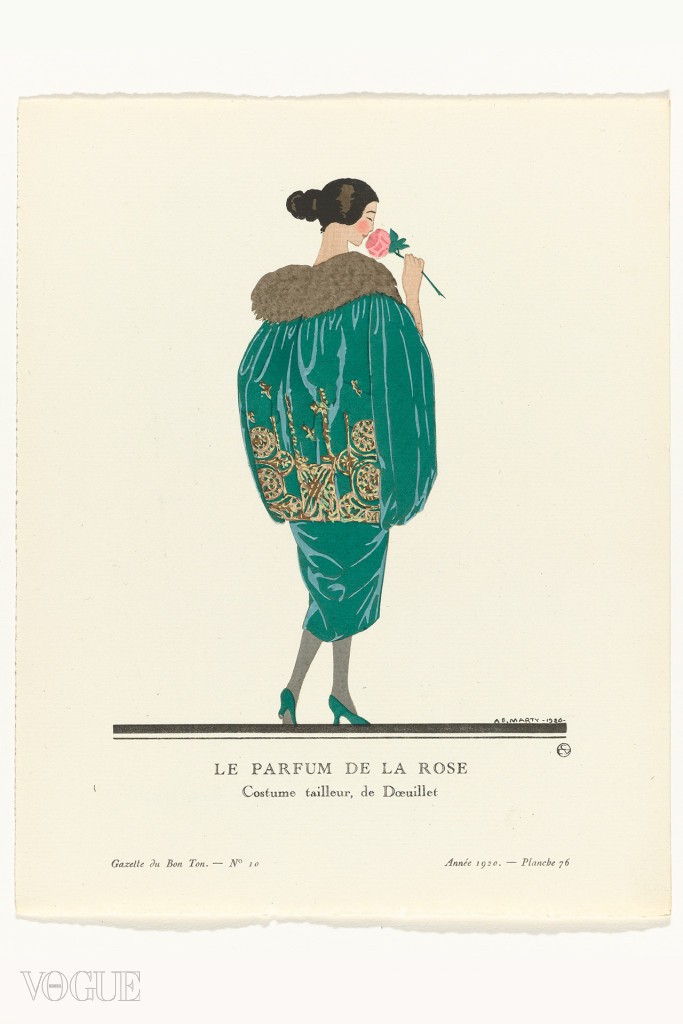

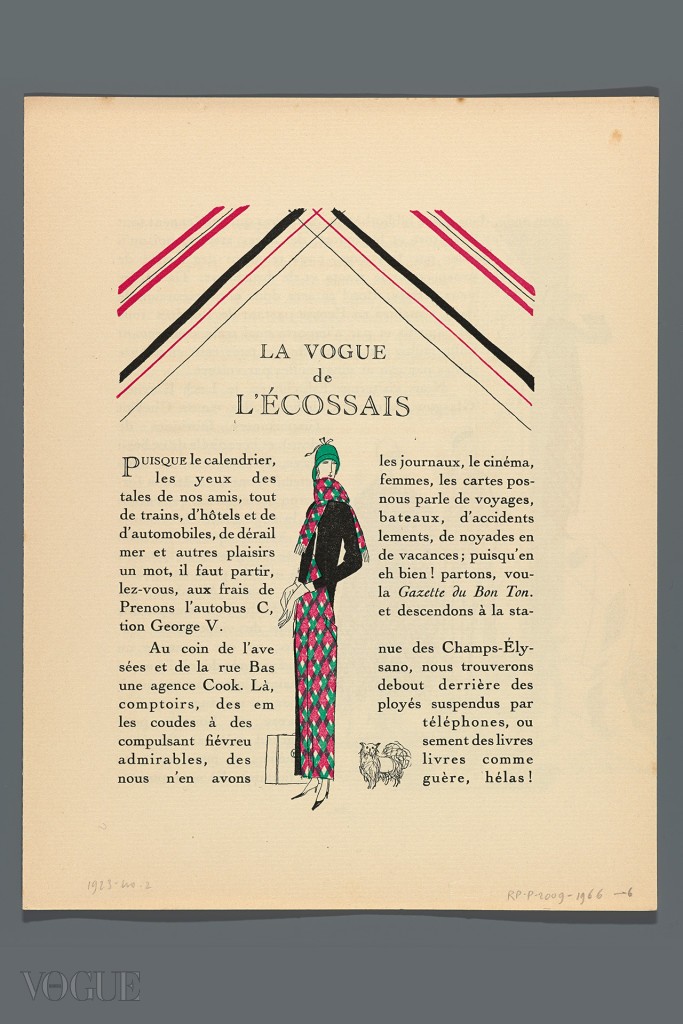

20세기 초반부터 유명한 이름들이 등장한다. 예를 들어 조르쥬 바비에, 라울 디퓌, 조르쥬 르파프 등 모두 20세기 초반 <가제트 뒤 봉 통(Gazette du Bon Ton)> 프랑스판에 실리던 일러스트레이션 작가들이다.

패션 일러스트레이션사의 초창기에 각 아티스트들은 우리가 중국식 버드나무 문양 그릇들에서 찾아볼 수 있을법한 작은 세계 같은 것들을 만들어냈다. 그럼으로써 언제나 의상들은 교태를 부리는 듯한 공원산책이나 완전히 뒤바뀐 가정환경이라는 문맥 상에 있게 되었다.

예를 들어 1801년 프랑스 혁명이 끝난 시기에 한 여성이 하이웨이스트의 심플한 드레스를 입고 나폴레옹 의자에 앉아 그리스 석고상을 스케치하고 있다.

전시회는 이 “세계 속 세계들” 덕에 작디 작은 벽 장식들이 달린 커다란 두 개의 방에 들어서며 가졌던 기대보다 훨씬 더 치밀하고 매혹적으로 느껴졌다.

<뉴 포 나우>와 패션 매거진의 시초에 관한 연구는 레이크스 미술관에 대한 두 집안의 기부 덕에 가능했다. 레이먼드 고드리오 컬렉션과 M.A. 게링 판 리어랑 컬렉션은 카메라 렌즈가 일러스트레이션을 패션계로부터 몰아내버린 20세기에 8000개의 드로잉을 수집했다.

큐레이터 엘스 베르하크와 미술관의 제너럴 디렉터인 윔 페이브스는 기부자들에게 감사를 표했다. 그러나 이 애호가들은 자신들이 컬렉션이 전시를 통해 얼마나 드라마틱해질지 상상조차 못했을 것이다.

화려한 피라미드형 가발에 금박장식이 달린 프록코트를 입던 남성들은 여성들보다 훨씬 일찍인 18세기에 호사스러운 의상들과 취향을 버렸다.

그리고 남성들이 심플한 의상을 선호하게 된 후 100년이 지나는 동안에도 가발과 보넷, 그리고 꽃무늬는 크로놀린 혹은 버슬 스커트와 함께 여전히 여성의 의상을 좌지우지했다.

전시 카탈로그에 실린 그림들은 상류사회의 스테이터스 쿠오(Status Quo, 현상유지)로부터 자유사회로의 드라마틱한 전환을 보여준다. 이 카탈로그는 앙드레 에두아르 마르티가 1921년도에 그린 일러스트레이션으로 끝을 맺는다. 이 그림에서 한 여성은 폴 푸아레 드레스를 입고 넓은 세상을 향해 창문을 열고 있다. 그리고 캡션에는 “Un peu d’air” 즉, 맑은 공기로의 환기라고 써있다.

궁중복을 입은 마리 앙투아네트. 체리빛 실크에 과감한 보디스, 여러 층으로 된 주름 레이스, 다이아몬드와 진주, 깃털과 리본으로 장식된 긴 옷자락으로 되어 있다. 앙투아네트는 양 손목에 팔찌를 하고 왼손에는 접힌 부채를 들고 있다. 의자 팔걸이는 도금이 되어 있고 등받이에는 왕관이 달려있다.

나는 이 작은 그림들로 이뤄진 전시회가 지닌 정신에 감명을 받았다. 이 그림들은 자유의 바람으로 가득 차있었다. 이 바람은 경직된 의상에 갇혀있던 신하들 사이에서 가장 먼저 불었다.

그러나 진정한 자유화는 여성들을 위해 이뤄졌다. 여성들은 섬세한 실내로부터 벗어나 해변가와 물놀이, 보트와 자유를 향해 움직였다.

되돌아보건대, 정원에 있는 여성들을 그린 초기 작품들 역시 자유에 대한 갈망을 표현하고 있었다. 이후 1916년도에 반 브록은 그아슈 물감으로 화려한 양산을 쓰고 공원을 산책하는 여성들을 그려냈다.

어떤 면에서, 이 일러스트레이션들은 카메라가 등장해 “현재로서는 새로운” 매체가 되기까지 드로잉의 마지막 발악이 되었다. 그리고 패션 일러스트레이터 피에트 파리스와 콴틴 존스 간의 최신 콜라보레이션은 전시회를 현대로 끌어왔다.

그러나 레이크스 미술관은 훗날 보그 및 다른 번득이는 잡지들을 탄생시킨 패션의 비주얼 에너지 중 대부분을 차지하는 근원을 보여주면서 패션계에 큰 선물을 했다.

<뉴 포 나우: 패션잡지의 기원>은 암스테르담 레이크스 미술관 필립스 관에서 9월 27일까지 열린다. www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/new-for-now

암스테르담 레이크스 미술관 전면에 드리워진 <뉴 포 나우> 전시회 배너

<뉴 포 나우> 전시회에서 전시 중인 일러스트레이션들

전시회장에는 푸른 잎이 무성한 포도카르푸스 나무가 장식되어 있다.

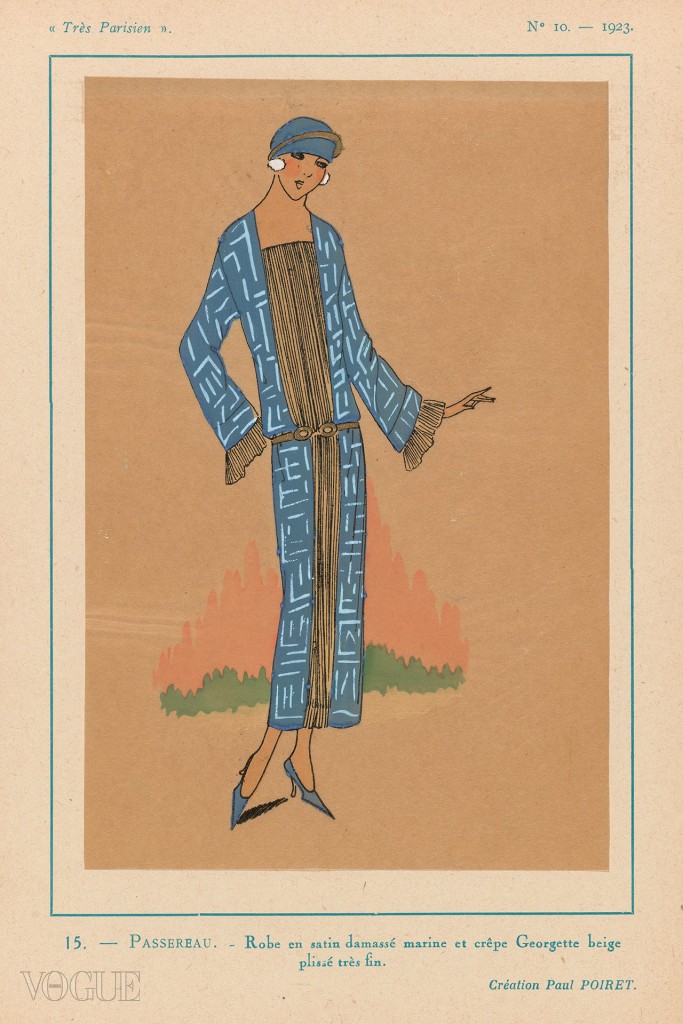

베이지색 섬세한 주름 조젯 크레이프가 들어간 네이비 블루의 능직 새틴 드레스. 폴 푸아레 디자인. 1923년도

프랑스식 예법 혹은 매혹적인 영국여성(1810-12), 손으로 채색한 판화

곱슬거리는 머리를 높이 고정해 리본, 장미, 그리고 다양한 종류의 깃털로 장식된 모자를 쓴 여성. 프랑스 헤어디자이너 드팡의 솜씨다. 보디체는 낮은 네크라인과 더블 칼라를 가지고 있으며 목에 스카프를 둘렀다. 1790년 <혁명 제 3기> 중 연작 <드팡의 헤어스타일> 일부. 에칭과 손으로 채색한 판화

오페라를 관람하러 온 1777년도 귀족 커플. 젊은 여성은 여왕의 궁전에서 궁중복을 입고 있으며 드레스가 너무 크게 부풀려있어 문을 옆으로 통과해야 할 것으로 보인다. 높이 올린 머리는 깃털로 장식되어 있다. 최신 유행을 따르는 젊은 여성들의 생활에 관한 시리즈 중 일부로 당시 프랑스 패션이 자세히 묘사되어 있다.

(위) 후드가 달린 숄더 케이프 (아래) 가발을 쓴 신사들. 두 그림 모두 1729년도

초록색 벨벳 이브닝 드레스를 입은 여성. 금박자수에 퍼 칼라가 달렸다. 쿠투뤼 드이예 작품, 1920년도 <가제트 뒤 봉통(Gazette du Bon Ton)>

1923년도 <가제트 뒤 봉통 - 아트, 유행과 천박함에 관해(La Gazette du Bon Ton. Art – Modes & Frivolités)> 중 스코틀랜드 패션에 관한 페이지. 루씨앙 보젤, 앙프리메리 스투디움 발간 16. 좋은 자세를 취하기 위해 흉갑을 두른 지도자, 1587년도 판화

좋은 자세를 취하기 위해 흉갑을 두른 지도자, 1587년도 판화

암스테르담 레이크스 미술관에 전시되어 있는 프리슬란트 제도 총독인 아우구스투스 스털링베르프의 초상 앞에서 수지 멘키스가 포즈를 취하고 있다. 1670년 로드베이크 판 데르 헬스 작품

겨울: 퍼 후드와 마스크, 퍼 토시를 한 여성. 1643년도 <포시즌스>, 벤체스라우스 홀라의 에칭

깃털과 장미모양 리본으로 장식된 데미보닛모자를 쓴 여성, 1787년

<뉴 포 나우> 전시회의 디스플레이는 포도카르푸스 나무의 울타리로 화룡정점을 찍었다.

English Ver.

Before there was Vogue

A new exhibition at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum looks at early fashion and costume prints and the development of fashion magazines.

He wore a plumed hat, a coat with ballooning sleeves, frilly pantaloons and fancy boots.

She balanced a chiffon headpiece above a voluptuous ribbon-bow bodice with a full skirt that spread over an entire sofa.

Well, it was the extravagant Eighties. The 1680s, that is – just before all the frills and froufrous were swept away, along with Louis XIV’s orgy of excess.

I saw that flash of the French Revolution’s history – which can be viewed as far more than a passing fashion trend – in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum where New for Now (until September 27) opens eyes and minds to history seen through pencil and paint.

The vogue for costume drawings – before there was Vogue – has produced a handsome and informative exhibition, which proves that you don’t need wild showmanship nor dramatic sets to bring fashion to life.

A line of green, growing bush of Podocarpus – a hint of playful sexual hide-and-seek games – is planted down the middle of a room by exhibition designer and co-curator Christian Borstlap where the stories of changing fashion and lifestyle are framed in the detailed drawings that preceded magazines.

The later names from the early 20th century are well known: for example Georges Barbier, Raoul Dufy and Georges Lepape, whose illustrations all appeared in the French Gazette du Bon Ton in the early 20th century.

Throughout the former centuries of fashion illustration, each artist created the same type of tiny world that you would find on willow-patterned plates. By that, I mean that clothes were always drawn in the context of a flirtatious walk in the park or in a transformed home setting.

For example, a post-French Revolution woman in 1801 sits in her high-waisted, simple dress in a Napoleonic chair, sketching a figure of a Grecian statue.

These worlds-within-a-world make the exhibition far more dense and fascinating than might be expected in entering the two large rooms with their tiny wall hangings.

Behind New for Now and its study of the origin of fashion magazines is a donation to the Rijksmuseum from two separate families – the Raymond Gaudriault Collection and the MA Ghering-van Ierlant Collection of 8,000 drawings collected during the 20th century, when the photographic lens pushed illustrations out of fashion.

Curator Els Verhaak and Wim Pijbes, the museum’s general director, both thanked the donators. But these art lovers could surely never have expected how dramatic their collections could be as a display.

Men, seen in the eighteenth century, their fancy pyramid wigs above frock coats festooned with gilded decoration, had their fancy clothes cut down to size and sense far earlier than women.

For another hundred years after men embraced sartorial simplicity, female wigs, bonnets and floral circles were still heading outfits with crinolines or bustles.

In the exhibition catalogue, the pictures show the dramatic switch from the status quo of high society to liberation. It closes with a 1921 Illustration by Andre Edouard Marty of a woman in a Paul Poiret dress, as she opens windows on the wide world. Its caption reads: un peu d’air – letting in fresh air.

I was struck by the spirit of this show of tiny pictures. They seemed impregnated with the wind of freedom. It blew first over the courtiers in their overwrought costumes.

But the real liberation was for women, as they moved from elaborate interiors to the sea shore, to salt spray, boats and freedom.

In retrospect, the early figures in gardens also expressed a yearning for a freedom that later grew into van Brock’s gouache-coloured engraving of women in a park with decorative parasols in 1916.

In one way, these illustrations were the last drumbeat of drawing before the invention of the camera made that medium “new for now”. And the collaboration with current fashion illustrators Piet Paris and Quentin Jones brings the exhibition up to date.

But the Rijksmuseum has done the fashion world a service by showing the source of so much of fashion’s visual energy which later impregnated Vogue and other glossy magazines.

New for Now: The Origin of Fashion Magazines is until September 27, in the Philips Wing of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/new-for-now

추천기사

인기기사

지금 인기 있는 뷰티 기사

PEOPLE NOW

지금, 보그가 주목하는 인물